Philippine Japanese Invasion Money

Japan’s wartime monetary strategy was designed to exploit the economies of occupied territories without imposing financial costs on the Japanese homeland. Prewar currencies—including the emergency notes authorized by the Philippine Commonwealth government—were declared illegal under threat of prosecution. In their place, local populations were compelled to use newly issued Japanese scrip. These notes were unbacked fiat currency, mass-produced, and imposed as the primary medium of exchange

In effect, Japan weaponized money. By issuing essentially worthless paper, they were able to pay for military campaigns, administrative operations, and resource extraction without offering real compensation to the local populations who supplied goods, labor, and services.

Japanese authorities were aware of the financial consequences of their policy but chose to overlook them temporarily in order to advance their wartime goals.

.jpg)

Frank Bond, U.S. Army Air Corps. The Photographer Kneels on a Street Littered with Japanese Invasion Money, Rangoon, 1945. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

1. Design and Denominations of JIM in the Philippines

Since Japanese Invasion Money (JIM) was fiat currency, it was not backed by precious metals like pre-war Philippine banknotes. Pre-war notes—such as those issued by the Philippine Commonwealth or the U.S. Treasury—often carried a promise to pay the bearer on demand and were issued with the intent of long-term stability, backed by gold or silver reserves.

In contrast, JIM was issued purely to support Japan’s wartime needs, making it a temporary currency meant to circulate only during the occupation. The first issues were printed in Japan under the direction of the Japanese military, but this responsibility was later transferred to the Bank of Taiwan, which managed issuance in the Philippines.

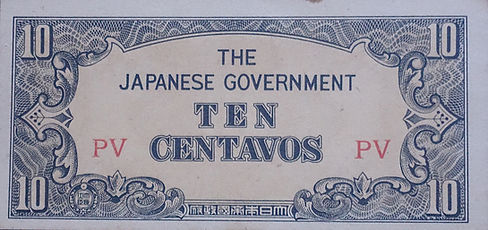

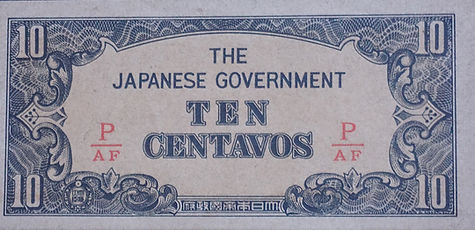

a. First Issue (1942)

The first series of JIM notes for the Philippines was introduced in 1942, shortly after the Japanese forces completed their occupation of the archipelago.

Denominations included:

-

1 Centavo

-

5 Centavos

-

10 Centavos

-

50 Centavos

-

1 Peso

-

5 Pesos

-

10 Pesos

The designs were simple compared to pre-war currency. The denomination appeared on both sides, with the inscription “The Japanese Government” prominently displayed on the obverse. From 50 Centavos to 10 Pesos, a recurring image appears: two boys riding a carabao in an abaca field—a likely attempt to connect with agricultural symbolism familiar to Filipinos.

Serial Numbers and Block Letters:

The first series used block letters as serial identifiers. These worked as follows:

-

The first letter “P” indicated the Philippines.

-

The second letter ranged from A to Z to track printing batches (e.g., PA, PB, ..., PZ).

-

When the sequence reached “Z”, a third block letter was added to continue the series (e.g., PAA, PAB, etc.).

To further expand the numbering system, Fractional Block Letters were introduced:

-

The letter “P” appeared above, and

-

A two-letter block appeared below, maintaining the same concept.

This system reflects how massively the notes were produced, emphasizing the scale of Japan's reliance on fiat currency to finance its occupation.

b. Second Issue (1943–1945)

The second issue of Japanese Invasion Money in the Philippines was introduced in 1943 and remained in circulation until the end of the occupation in 1945.

Denominations issued:

-

1 Peso

-

5 Pesos

-

10 Pesos

-

100 Pesos

-

500 Pesos

-

1000 Pesos

This series continued the minimalist design approach, but introduced notable changes in imagery. The abaca scene used in the first series was replaced by the Monument of José Rizal, a national hero of the Philippines—possibly intended to add legitimacy or local familiarity to the notes. However, the 1000 Peso note was an exception and featured a different generic decorative design, with no specific local landmark.

Serial Numbers and Printing

The second issue also introduced numerical serial numbers, while some denominations still retained the traditional block letter system from the first series.

2. Higher Denominations and Wartime Inflation

a. Inflation Under Japanese Occupation

As the Japanese occupation progressed, the Philippines experienced severe inflation due to the over issuance of fiat currency—Japanese Invasion Money (JIM).

The economy was flooded with unbacked paper notes printed by Japanese authorities to fund their military and administrative operations.

Prices for goods rose rapidly, and the real value of the currency steadily declined.

In addition, many civilians were reluctant to use the currency, recognizing its lack of intrinsic value and distrusting the occupying forces behind it. This loss of public trust contributed to the weakening of its purchasing power and further destabilized the local economy.

b. Impact on the Philippine Economy

Despite escalating inflation, hyperinflation did not fully materialize, and the economy—though strained—continued to function.

According to Huff & Majima (2013), this was due to three main factors:

-

Sustained transactional demand for money: Civilians continued to use JIM out of necessity.

-

Strict monetary enforcement by the Japanese military: Alternatives such as prewar notes or guerrilla currencies were banned under threat of punishment.

-

Japan’s declining logistical capacity to extract resources from the Philippines: This slightly reduced monetary pressure over time.

c. Introduction of Higher Denominations

To manage inflation and maintain functionality in daily transactions, Japan introduced higher-denomination notes.

Their issuance reflects both the magnitude of inflation and the Japanese government's continued reliance on fiat money creation as the war drew to a close.

3. Allied Counterfeiting

As part of the broader Allied war effort against Japan, General Douglas MacArthur authorized the counterfeiting of Japanese Invasion Money (JIM).

In the Philippines, this operation served two primary purposes:

-

To destabilize the local wartime economy under Japanese control

-

And to fund guerrilla resistance movements fighting behind enemy lines

However, the Allies did not counterfeit all JIM notes indiscriminately. Instead, they focused on specific block letter combinations to blend forgeries into legitimate currency in circulation.

According to a list of known counterfeits documented on Wikipedia, the following blocks were targeted:

-

50-centavo bills: PA, PB, PE, PF, PG, PH, PI

-

1-peso bills: PH

-

5-peso bills: PD

-

10-peso bills: PA, PB, PC

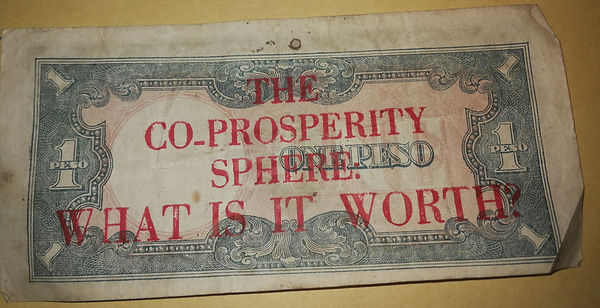

Psychological Warfare

Beyond forging currency, the Allies also employed JIM as a tool for psychological warfare. Some counterfeit notes were overprinted or labeled with provocative messages such as:

“The Co-Prosperity Sphere: What is it worth?”

These notes were air-dropped over Japanese-occupied areas to undermine confidence in the occupation currency and mock the promises of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Today, notes with these overprints are particularly valued by collectors for their historical and propaganda significance.

Counterfeit 1942 5 Peso JIM

Image Source: Japanese government-issued Philippine fiat peso with overprinting. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

4. Collector Reference and Resources

For collectors and researchers interested in Japanese Invasion Money (JIM) in the Philippines, a valuable resource is the Numismatics.ph: Japanese Invasion Money Catalog.

This catalog provides:

-

A list of JIM issues specific to the Philippines

-

Reference images for both genuine and counterfeit notes

-

Details on Allied forgeries and tips for identifying them

Whether you’re studying serial formats, comparing design changes, or verifying propaganda overprints, this catalog offers insights grounded in historical and numismatic research. It’s an essential tool for anyone seeking to understand or collect these notes beyond face value.

a. Pricing and Market Trends of Japanese Invasion Money

Japanese Invasion Money was produced in massive quantities during World War II, making most surviving examples relatively inexpensive for collectors today.

However, prices can vary widely depending on a note’s rarity and availability.

The most common factors influencing value include:

-

Condition (Grade) – Crisp, Uncirculated (UNC) notes command significantly higher prices than circulated examples, yet they remain relatively affordable for most collectors.

-

Denomination – Higher denominations, such as ₱500 and ₱1,000, are much scarcer and often sell at a premium.

-

Block Letter and Serial Number – Certain print runs, identified by specific block letter and serial number combinations, are rarer and therefore more sought after by collectors.

-

Overprints and Propaganda Notes – Notes featuring wartime propaganda messages or overprints, especially those dropped by the Allies, are highly collectible.

b. Nearly Minted Occupation Coins

During World War II, Japan had plans to extend its monetary control beyond paper notes—including issuing coins in occupied areas like Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak, and Brunei.

However only pattern (prototype) coins, such as the rare 1942 Malaysian aluminum 20-cent designs, were produced.

The existence of these pattern coins underscores the broader scope of Japan’s monetary ambitions within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (GEACPS)—showing intent to replace local coinage alongside invasion banknotes.

Image Source: The Malaysiana Collection's (Facebook Post) - Click here for view the full post. View certification at NGC Cert Lookup

Sources & Further Reading:

1. Huff & Majima (2013) Working Paper: Financing Japan’s World War II occupation of Southeast Asia

2. Britannica.com: Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

3. Wikipedia.org: Japanese government–issued Philippine peso

4. Wikipedia.org: Japanese invasion money

5. papercoinage.weebly.com: Philippines - Japanese Occupation Note's - WWII

6. Numismatics.ph: Japanese Invasion Money Catalog.

8. The Malaysiana Collection – Facebook post, Febaruary 2025.

Published Date: 8/11/2025